My name is Suellen, I'm Brazilian, and I was born in São Paulo in 1997. That same year, the Zapatista Movement organized a march that took over the streets of Mexico. On April 15 of that year, Brazil's Landless Workers Movement (MST) took 40,000 people to the streets of the city of Brasília to protest against the government of the then-president, Fernando Henrique Cardoso.

In Vedic astrology, my Nakshatra is Vishakha. This means that, if there's one word that can describe me, it's "determination." I put all my dedication into achieving what I want. That's why I must choose a reason. After that, I just put all my energy into it. I behave in a very loving and respectful way towards people. If someone needs me, I always go to their aid.

This won't be the first and only time I write in the first person. Firstly, because I'm taking on the role of storyteller – and, in this craft, we often narrate the experiences and memories of others. Secondly, I feel in my heart that this work is about living in the present, preserving what came in the past, and looking after what will come in the future; which is not done alone: the result is collaborative. Marginal Fiction is a curatorial project that strives to map, share, and care for Latin American dreams. Therefore, sometimes I'll be Maria, Jorge, Juan, Isabel, or Rosália. Never just an object of study, often the one telling the story.

From Argentina's South to Mexico's Northern borders, people live and tell the stories of others daily, whether through oratory, a bar chat, or sermons from grandparents to grandkids. I'm very interested in the lives of ordinary people. The knowledge and culture that move and expand like the Andes Mountains on the outskirts of South America fascinate me.

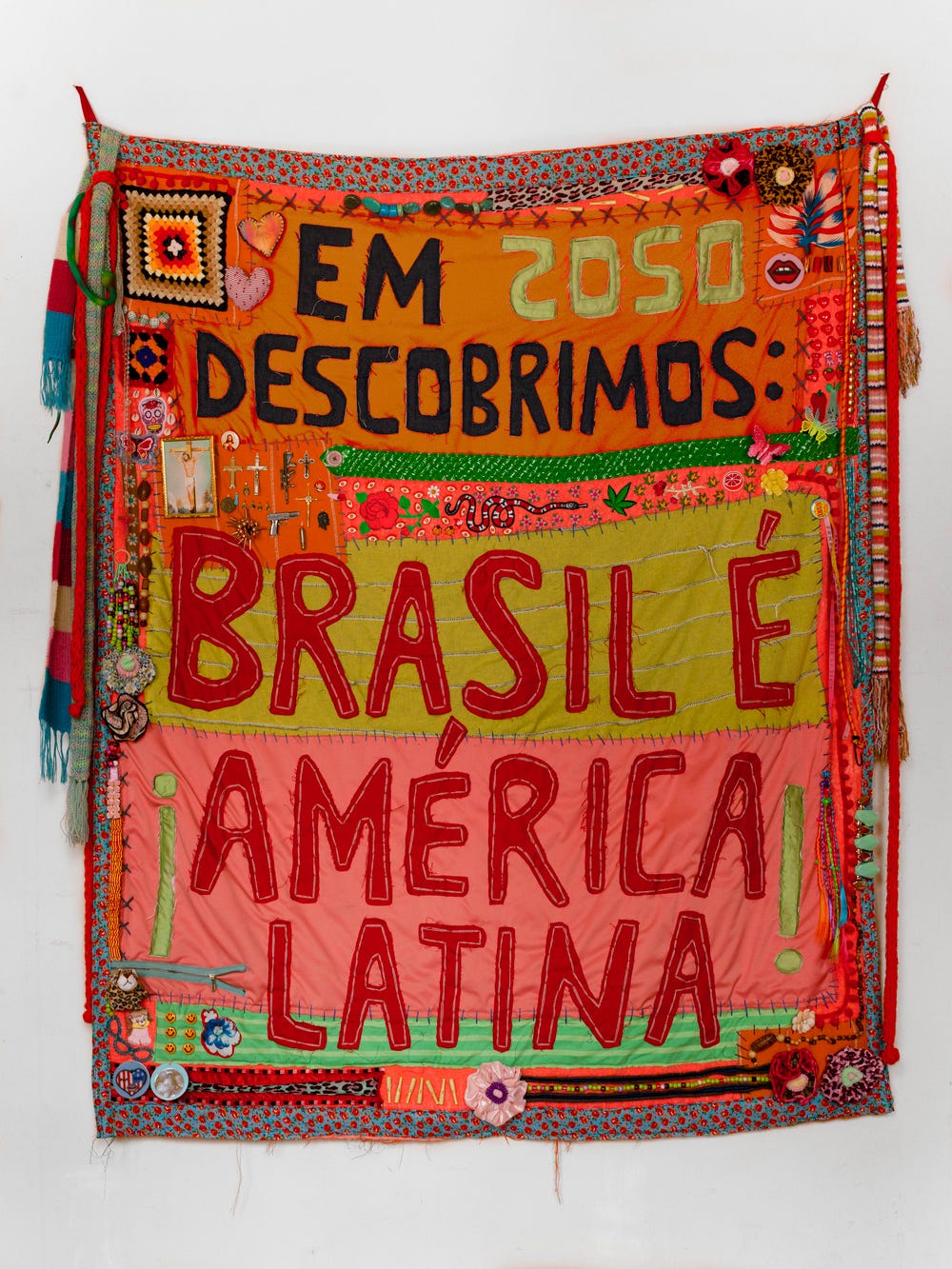

"Latin America," which was once simply words, but has since solidified into the idea of a single culture to establish a continental identity, is dropped here. And, joining Miguel Rojas Mix's chorus, I agree that "the history of Latin American identity is also the history of the various names of the American continent and the reasons why these names were imposed."

The plurality of the Global South is often homogenized in such a way that the North continually manages to appropriate our lands, people, and imaginaries. The idea of a single culture was born out of a process of exploitative colonization that continues to this day in the narratives of the North.

The ones who are up there are the "developed" ones. They exploited, stole, killed, raped, murdered, and, to this day, maintain political and economic domination over us (those who are down here). This process happens in such a manner that we don't notice their crimes disguised as progress. Peace in the North costs us dearly. They have made us emergent and marginalized.

When we take ownership of our narratives and get closer to each other, we become capable of understanding, defending, and preserving our stories. In Brazil alone, there are more than 270 indigenous languages; we also speak Portuguese with spices (accents) from the states of Ceará, Amazonas, Goiás, São Paulo, and Bahia. We have six biomes with distinct characteristics that form different food cultures and human and environmental relationships. There is a world within each country, and there are 30 more countries within each city.

I, who have traveled to all four corners of this land, can now see why they are suffocating us to the point of mutt complex: we are a powerhouse, but by now you should already know this. For this and other reasons, they continue to tell our stories from a global, Eurocentric, and outsider perspective – it's strange, doubtful, fearful, and indignant. In this sense, the anger of the marginal people emerges from an open wound in the middle of Latin America, bringing the voices, dreams, and stories of others through this project.

Pedro Lemebel, who echoed the tradition of orality through his rebellious and transmodern writing against the Chilean dictatorship, inspired me to write like someone who enchants and stimulates the chaos. Ana Tijoux taught me how to bring out my lifeless voice and create an orchestra. I let the words resound in the breeze on the coast of Brazil, in the land of Saint Salvador, as I find new means of curating what cannot be kept in a museum.

The memories and lives of Brazilians are as heroic and fascinating as those of the great knights clad in steel armor and depicted in gold-framed paintings in palaces throughout our territory. I once met a retired Brazilian teacher in a hostel in Bogotá; his beard and very whitish hair were eye-catching. While packing a backpack, he cocked his head, and his glasses wisely slipped down his nose, lending an appearance of seriousness to what he was about to say to me. Looking at me over the lenses, he advised:

— Girl, there are three things you need to know in life to live anywhere in the world: cooking, swimming, and speaking English.

That man, a former public-school teacher in Brazil, told me that he had pursued his job his entire life and had supported his children on his pay, but that, at that point in his life, he needed to achieve his goal of backpacking wherever his heart allowed.

I'll never forget that man or his lessons. I wished I had more time to listen to his stories and hear about his loves and sorrows. I'm sure he'll never know that our chat moved me to such an extent that I started swimming lessons, learned to cook, and hired a private English teacher.

I spend most of my life traveling, and many stories have been passed down to me in shared rooms, bars, museums, boat trips, and long walks at dawn. All of these stories are beautiful – even the most horrific among them. There's an entire universe inside each individual, and we become even more sensitive when we look through the anthropological lens that makes up the network of facts that a person has traversed.

The Latin American dream

If we once desired the American (US) dream, we now envision the Latin American dream. The movie Map of Latin American Dreams depicts the story of a Cuban bootblack who aspired to be a poet, but died months before filming began in Cuba. His wife's testimonial provides a beautiful story of love and coexistence about her husband, who, despite his desire to write poetry, never showed her any of his verses because he was embarrassed by his handwriting.

A friend of mine, a young yoga teacher from Rio de Janeiro, told me that his dream is to live well and earn well from his work; communicating, creating content, and presenting an audiovisual program that also helps people live better lives, despite the social structure that prevents us from doing so. He wants to make well-being more accessible because he believes that we deserve to live better.

Randolpho Lamonier l Prophecies

My mother, a migrant in São Paulo who came from the northern region of the Vale do Jequitinhonha, state of Minas Gerais, has already confided to me, her eyes welling up with tears, that her dream was to visit Ouro Preto, a city only 10 hours from where she was born and spent her youth.

Some dreams go further. José M. Hernández, the son of Mexican immigrants, was turned down more than 10 times before he could go into space. As a niño, Hernández was fascinated by the stars and space and had a big dream in mind: to become an astronaut. His story was told in the movie A Million Miles Away.

In many cosmologies, dreams play an extremely important political role in the community. It is from them that decisions are made, things are created, and the invisible and visible worlds become one. Dreams are real experiences, whether we are awake or asleep. From them comes the wisdom needed to create desirable futures.

My dreams are verbs: to hope and to write. By curating – this craft of preserving and telling narratives –, I challenge myself to delve deeply into the knowledge and experiences that intersect in Latin America.